After a Good Night’s Sleep Brain Cells Are Ready to Learn

Stephanie Dutchen, National Institutes of Health

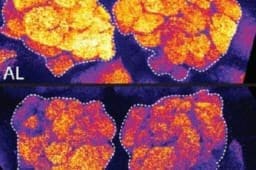

On top, the brain of a sleep-deprived fly glows orange because of Bruchpilot a communication protein between brain cells. These bright orange brain areas are associated with learning. On the bottom, a well-rested fly shows lower levels of Bruchpilot, which might make the fly ready to learn after a good night’s rest.

On top, the brain of a sleep-deprived fly glows orange because of Bruchpilot a communication protein between brain cells. These bright orange brain areas are associated with learning. On the bottom, a well-rested fly shows lower levels of Bruchpilot, which might make the fly ready to learn after a good night’s rest.

CREDIT: Chiara Cirelli, University of Wisconsin-Madison

This Research in Action article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

Why do we need sleep? Some researchers think it gives our bodies a chance to repair themselves. Others think it gives our brains time to organize our thoughts. Neuroscientist Chiara Cirelli at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and others believe that a good night’s sleep helps us learn more the next day.

When we learn, synapses — the connections between our brains’ neurons — grow and multiply, consuming more fuel, said Cirelli. But our bodies can’t handle unchecked growth and energy consumption. Sleeping slows brain activity and may return our synapses to a less excited state, she said, refreshing and preparing us for more efficient learning in the morning. Conversely, insufficient sleep may fail to reset the synapses and leave us feeling “wooly-brained” the next day.

Cirelli calls this daily rejuvenation “synaptic homeostasis.” She has been testing the hypothesis in animal models such as rats, mice and fruit flies in the hope of bringing us one step closer to explaining why we sleep.

The images above show the results of one of her experiments. On top, the brain of a sleep-deprived fly glows orange. The color marks high concentrations of Bruchpilot, a synaptic protein involved in communication between neurons. The color also lights up areas of the fly’s brain associated with learning.

On the bottom, a well-rested fly shows lower levels of Bruchpilot. The study suggests that sleep reduces the amount of Bruchpilot in fly brains, which might reset the brain to normal levels of synaptic activity and make the fly ready to learn after a good night’s rest.

A more recent experiment by Cirelli’s group showed that the branching ‘fingertips’ at the ends of neurons grow longer and make more connections with other brain cells after flies spread their wings for the first time. These ‘fingertips,’ or dendrites, then get “pruned” at night when the flies sleep, again getting them ready for a new learning experience the next day.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.